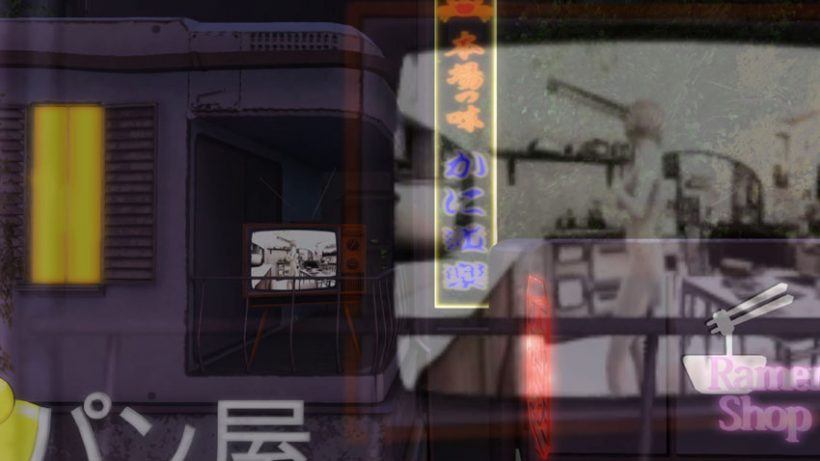

In Amelie Marcoud’s installation Hikari* stacked televisions displayed repeated images in endless loops. My latest machinima, Repeat Hikari, took the looping repetition and hesitations of the installation, and reworked them with the hesitations and jumps of video editing.

Apart from being a deliberate choice, short loops reflect to the technical limitations of Second Life. Looping textures get round the difficulty of streaming video into Second Life. Short animation loops for objects, including avatars, are less demanding on memory.

But the looping images showing on the screens draw attention to the animations that make the trees and my ‘human’ avatar move. These animations seem ‘natural’ while half-watched, but become as mechanical as an a Victorian automaton when watched carefully. This is emphasised by the little stoppages that happen when the cycle of animations ends, then restarts from the beginning.

However, many artworks in Second Life are set up as a tableau of static poses. They often serve some kind of authorial narrative, be it explicit or implicit, in summary or in detail. But to me, the frozen poses often feel like a dead hand pointing out the way through. Yes, you can choose not to go that way, but actions are always weighted with obligations. It’s the same as abandoning a book or walking out on a film or theatre production. It is not a morally neutral act and it takes an attitude of mind to do it.

Narratives are inevitable, but need not ‘drive’

In Hikari, there was always something going on, without any need to tell someone what to do or think. You could wander, watch, move on, return, without the hot breath of narrative expectation on the back of your neck.

In my video work, I rarely use an overt narrative. Narratives are always there, because we make them up for ourselves as a way of making sense of the world. And I recognise that I can never completely step away from that. Making any kind of timeline is inevitably a narrative of some kind.

But a short video is more like a prolonged still image, as the vision (and sound) can be held in the mind as a single piece. That said, I’m not saying it is somehow outside of time. It still takes time to view a still image, just as it does to watch a moving one.

And the editing process of film (or video) is a deliberate play with time. The discovery that audiences didn’t need a continuous unbroken timeline revolutionised cinema in the early 20th century. The editing process is one of resequencing and time-shifting, of establishing and breaking connections. And this is why I prefer the term ‘editing’ to the US term of ‘cutting’, as cutting only describes one part of the process.

Mood and feeling

Edits are dependent on the words, images and meaning that come before and after them. But they are not just blank spaces or mere transit points. The style of the edit, slow and blended, or fast, or with a gap, also establishes a mood, suggesting connections and leaving space for thought.

Some artworks create a feeling or mood for me. Perhaps resonance is a better word. Resonance implies both sound and vision, both of which are important. But resonance also results from a light touch – a tuning fork or a bell won’t ring if it is held tightly. Equally, when an artwork is held tightly into a narrative, it says what it is allowed to say, and no more.

To make a machinima, I want the space to interpret and say something beyond the original artwork – to add, not because I think the original was inadequate, but because the artist gave room to continue. A recognition of the value of open-endedness in creativity.

* Hikari was an installation constructed by Amelie Marcoud. It was located at The G.B.T.H. Project (curated by Marina Münter and Megan Prumier) until 25 July 2018.

2 thoughts on “The art of looping and repeating”