I was watching an interesting video recently about a new game that’s now just been released, Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, made by The Chinese Room. Dan Pinchbeck, the Creative Director, and Jessica Curry, the Studio Head/Composer, talk in the video below about how players ‘discover story’ through finding electrical devices to interact with in the scene, and not by the game design ‘dropping story in their path’ as they go. The game is intended as a personal journey; it is ‘your responsibility’ to find the stuff and uncover story. True, there is a single narrative, but it is one to discover through exploration, rather than there being a branching narrative controlled by the game creator who directs and redirects the progress through cut scenes.

I have discussed in a previous post about the importance of the cut in making sense of the flow of time, and how it is not just a feature of editing, but also a sub-conscious process. The critical issue here is who makes the cuts, and if it is the ‘player’, how freely they can make them. In games, there is a structure of rules that establish a ‘moral’ imperative to to meet the goals1 by following the rules as stated. The goal may be a prize or points, or the satisfaction of solving a mystery. Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is sold as a game, even if it is deliberately generous with space in order to avoid the bam-bam-bam succession of events in more typical computer games. In that context, Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is free-form, but not free play. It can perhaps be seen then, as positioning itself between game-playing and living.

This blurred area between games or life is something I’m interested in; it’s what Virtual Worlds do particularly well. Play is a part of culture; in the Forward of his classic book Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture1 Johan Huizinga emphasises that he wanted the title of his book to be translated (from the Dutch) as ‘the play-element of culture’, not in culture. Culture is a process, not a conclusion, if you take Raymond William’s view2. Play is not embedded in life like a cherry pushed into the icing of a cake, but rather it is an inherent part of the flow of life.

Erving Goffman, in Fun in Games3, argued there were a series of definitions around the game, which created distinctions between game, play and gaming. The game is the set of rules, and play is an instance of the game being run from one end to the other; this is the game as a discrete activity conducted in a space set voluntarily, freely and temporarily apart from other activities of life. Gaming and the gaming encounter are social situations within a focussed gathering, where the boundary between the game and life is porous, an ‘interaction membrane’4. In the case of virtual worlds, one enters the ‘game’ as an extension of ‘life’ before then starting to ‘play’ within it; it is very porous.

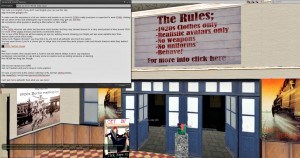

Taking Second Life as a gaming encounter, I’d suggest the two most obvious types of games that are played within it as games are roleplay and hunts. In the roleplay sims, you are handed a set of rules on landing. There is clearly flexibility to develop interactions and narratives independently, but it is within a defined and mutually accepted framework. Visitors are asked to behave in particular ways that fit in (or at least don’t stand out) and players who break the rules will be ejected.

Hunts have a clear objective; to gather information or objects. Both conform to Huizinga’s arguments about moral structures – one is supposed to conform to the the rules or you will be ‘called out’. However, these moral codes of ‘should’ and ‘ought’ are not contained within the game; they have ‘leverage’ within the mind of the player and their desire to socially conform, or to express individuality, personal opinion or rebellion.

As with real life, moral codes are not just commonsense, they are assumed conventions that those with power and social status have a greater ability to control or promote. While game rules are accepted as a temporary condition of being in a game, within the wider experience of Second Life as a gaming encounter, these conventions become more questionable.

Why, for example, do nipples make the difference between General and Mature ratings, irregardless of how sexualised a female form is?5 What about racial prejudice and issues of skin colour?6 Questions around age-play?7

These are not issues not confined to any particular game or place; these are questions about social life and human culture that vary in context and form in debates across time and space.

- Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1949) <http://art.yale.edu/file_columns/0000/1474/homo_ludens_johan_huizinga_routledge_1949_.pdf>.Charles Wankel and Shaun K. Malleck, Emerging Ethical Issues of Life in Virtual Worlds (IAP, 2010).

- Raymond Williams, Culture and Society 1780-1950. (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1961).

- One of the two essays in: Erving Goffman, Encounters: Two Studies in the Sociology of Interaction (Bobbs-Merrill, 1961).

- Erving Goffman, Encounters: Two Studies in the Sociology of Interaction (Bobbs-Merrill, 1961), p.65.

- https://community.secondlife.com/t5/English-Knowledge-Base/Maturity-ratings/ta-p/700119

- Carleen D Sanchez, ‘My Second Life as a Cyber Border Crosser’, in Women and Second Life: Essays on Virtual Identity, Work and Play, ed. by Julie Achterberg and Dianna Baldwin (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co Inc, 2013), pp. 63–76. See also the range of skins in the featured image.

- Charles Wankel and Shaun K. Malleck, Emerging Ethical Issues of Life in Virtual Worlds (IAP, 2010).